Articles

The wake up stick

|

Located almost at the summit of the mountain in Kwan Ju, South Korea, the Soen [Zen] monks [Bhikkhus] and Lady monks [Bkikkhunis] at Hua Om Sa wake hours before dawn to the sound of a bell or sometimes a wooden clapper being sounded near their sleeping quarters. Typically, the wake-up call would come at 3 am. In the chilled darkness of early morning, the Bhikkhus and Bhikkhunis pull on their outer robes and make their way to their respective gathering places for morning chanting and meditation. |

|---|

Between the extremes of austerity and sensual indulgence

In the Buddhist tradition, maintaining a tight but not intolerable discipline is expected in temples. 'The Middle Way, Majjhimā Paṭipadā is the term that the Buddha used to describe the character of the path he had discovered that leads to liberation.' Wikipedia It is sustainable, whereas extreme practices are not.

According to the Pali Canon of Theravada Buddhism, the expression 'The Middle Way' was used by the Buddha in his first discourse (the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta) to preface his teachings and to describe the 'Noble Eightfold Path' as a path that lies between the extremes of austerity and sensual indulgence. This is the meaning that I am focusing on here.

The monitor monk and his wake-up stick

Given our different backgrounds and preferences, one man’s middle way may be very difficult for another to follow. Waking up three hours after midnight and walking through the cold darkness to the main hall to meditate is not the easiest thing for many people to do, and at 3 am, many of the monks at Hua Om Sa were still sleepy and consequently sometimes dozed off during the morning group meditation session.

This is when the monitor monk became so important.

|

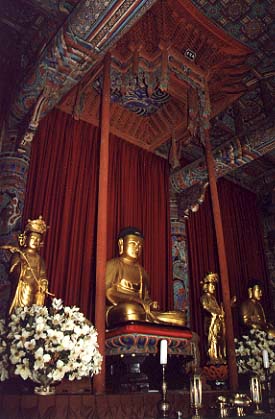

In the spacious high-ceilinged wooden hall, with the colourfully-painted interlocked beams barely visible above him in the candle light, the monitor monk walks up and down the neat rows of meditators. He is wearing baggy, grey pyjama-like robes and carrying a double-layered polished wooden tube about two feet long and one and a half inches wide. This unique instrument is used to awaken sleeping meditators. It is hollow. The outer layer is incised with long slits cut along the length of the tube. The inner layer does not have these slits. If you hit thetube against something, it emits a resounding ‘crack’. |

|---|

The monitor monk’s job is to notice anyone who appears to be about to fall asleep and to hit him from the back across his shoulders. The slits in the wood ensure that the blow will produce a reverberating whack but not cause any major physical damage. The shock of the blow ensures that the sleepy meditator is very unlikely to fall asleep again any time soon during formal meditation.

A monitor monk is highly respected. His job is to be the awakener. Formerly-sleepy meditators will come to him after the session to thank him and to pay him respect.

Crocodile pools

Awakenings may be triggered similarly unpleasant experiences that rouse us from our habitual sleepwalking-like ways of interacting with the world. The triggers might for example be tripping up while walking down a street, failing an exam for the first time, a girlfriend or boyfriend losing interest or a fear-inducing news story. When things are going well, we are content to remain as we are. There is no motivation to wake up.

Zen monks, famously (in Western movies at least) set up situations where fear would keep people awake. These included meditating on a ledge at the top of a cliff or on a rooftop. Another anecdotal keep-awake scenario was to meditate on or walk across a narrow plank thrown across a pool containing crocodiles. There might be something in the stories but I think Zen practitioners in Japan and China might have had to import their crocodiles from elsewhere.

When we perceive an imminent threat, our system gets a shot of adrenaline. Our senses become heightened and focus is directed to the ongoing situation. We seek a way to escape the danger or somehow deflect it. When that sense of heightened presence is directed to interactions in the ordinary world, even a simple act of opening a door can become a life-changing experience.

It is only in the present that a person can be fully-engaged. Someone who is fully-engaged is awake to the present.

Woken up to reality

Although satisfactory translations from one language to another may not always be possible due to different ranges of understanding derived from disparate cultures, it is sometimes useful to look at pivotal concepts and how they are expressed in language. According to some translations, ‘Buddha’ means ‘Enlightened one’ or ‘Awakened one’. In the Theravadan tradition, it designates a great spiritual teacher and as such it predates Sakyamuni Buddha – the Buddha whose awakening initiated the forms of Buddhism that still exist today. ‘Muni’ means a great sage. ‘Sakya’ refers to the Sakya clan from northern India and Nepal. So it means the great spiritual teacher (= sage) from the Sakya clan.

The term “Buddha” is an honorific, meaning ‘Awakened One’. It had a range of meanings in ancient India, but it came to mean one who has awakened from the sleep of ignorance and achieved freedom from suffering. Paraphrased from A comparative dictionary of the Indo-Aryan languages. London: Oxford University Press. Digital Dictionaries of South Asia, University of Chicago. p. 525.

The word ‘Buddha’ is a title, not a name. It is derived from the Sanskrit: “Budh,” to know. It means “one who is awake” in the sense of having “woken up to reality”.

Waking up

Have you ever opened your eyes in the morning and although your surroundings are familiar and conform to what you would expect to see around you after a night’s sleep, you are still partially in the state of mind that you had been in during a recent dream. The dream state seems at least as familiar and current as the familiar surroundings in the room. Your attention can, for a few seconds at least, engage with the familiar norm or with the dream state.

Can you then, by analogy, imagine a state of being that is at a more profound level of awakening? One that is as different from the familiar and consensually agreed upon view of what is real as the dream state was to the everyday waking state.

Suddenly your physical senses can play out a range of sensations, thoughts and understandings that are no longer restricted to familiar scales and accepted modes of combining the various notes. Suddenly you are playing symphonies of experience that lift you profoundly beyond the mundane. The ways in which you previously experienced being fade back into washed out pale insubstantiality.

This unbidden wake-up experience is as likely to happen in a city street as in the gilded halls of a temple. If the mind is clear and open, it can happen anywhere.

If the mind is cluttered up with distractions and long-standing habitual reactions or dulled down by old conditioning, awakening is unlikely to happen.

For most of us, our state of mind is not constant. Sometimes it can be quite peaceful and, at other times, it can be disturbed and distracted.

The great thing about these shifting states of mind is that they can be ‘shifted’.

They can be shifted by awareness of what is going on in any present moment. This simple focused awareness is not like an eraser to delete parts of yourself, however. Neither is it a cover up. If you assume a different way of behaving without dealing with underlying tendencies, you will, in effect, be an actor. The old you will still be there beneath the new persona. Externally-imposed discipline may not sit well with you. The intellect may see the advantages of behaving in a different way, but other levels of your being may feel imposed upon and subvert your best efforts towards self-improvement.

Digging around in your memories, sifting through them for clues as to why you feel a certain way may sometimes help.

If these approaches work for you, please continue them. In case, if at some time in the future, you wish to try a different approach, I’ll mention here a ‘prescription’ that has been found to be effective for over two and a half thousand years.

Awareness of the stream of mind moments

All you need is your body and mind, and at the beginning anyway, a place where you will not be disturbed by loud noises or other interruptions.

In the present crowded and clamorous world, you may need to be quite creative to find such places. As a student, working though the summer break, I once worked as a temporary sales assistant in a large central London department store. The only relatively undisturbed place I could find was the roof. So, after climbing several flights of dusty, seldom-climbed stairs, I would wedge open the heavy fire-escape door and tune into the present, accompanied by flocks of curious pigeons, on the flat grey concrete roof amidst long-abandoned items of furniture.

As the muted sound of the traffic, many floors below, faded into a distant hum, I would close my eyes and allow whatever I sensed to come, be perceived, go though its changes and eventually pass away in its own time. The same process happened with thoughts and emotions. They were allowed to be there, go though their changes and pass away. Each one, when known, came to its end. The tendencies in me that had fired their importance also came to an end. They were swept away by focused, non-judgmental awareness of the stream of mind moments.

When such tendencies are seen clearly, the meditator’s job is done. Those tendencies will have been reduced in their effectiveness to control or disturb - and may have been removed completely. Little by little, moment by moment, past accumulations are reduced and the mind becomes lighter and clearer.

The natural mind is light, clear and awake. You do not need to add anything to it. You do not need to become somebody else. You do not need to better yourself or do some kind of spiritual makeover. The process described above allows you to experience being awake to each fathomless moment of your now.